How to Start Investing in a World-Class Whiskey Collection, According to Experts

Scotch alone has surged in value by a whopping 564 percent over the last decade.

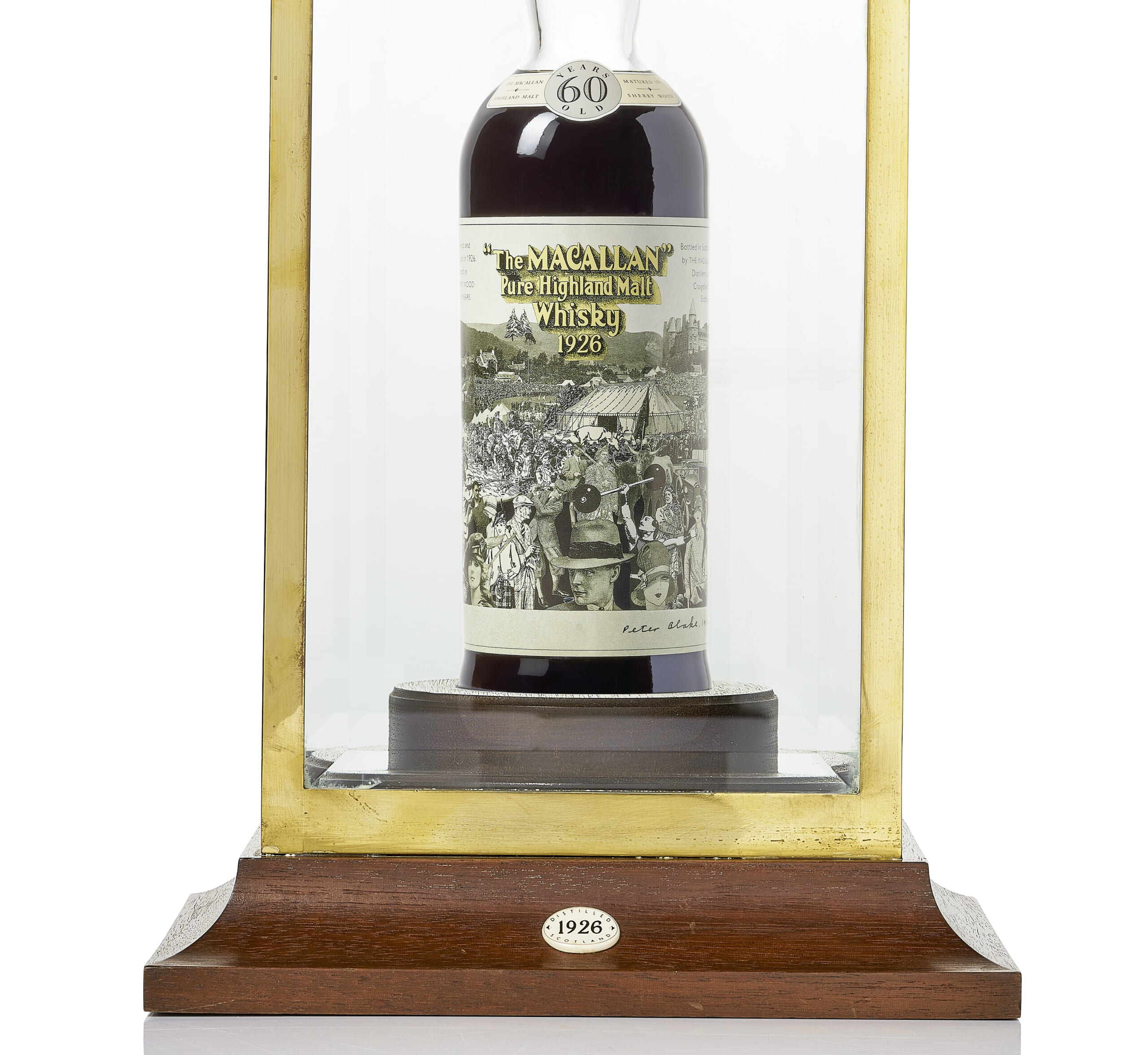

Last October the $1.9 million sale of a bottle of The Macallan single malt Scotch distilled in 1926—the highest price ever paid at auction for a bottle of spirit—made even those who never touch the stuff sit up and take notice. At 700ml, it contains about 45 pours, making each dram worth around $42,000.

Martin Green, Whisky Specialist for the storied Bonhams auction house in Edinburgh, Scotland, and one of the world’s foremost experts, was, however, hardly surprised. “For the past two years, Scotch whisky has been making headlines around the world as never before,” Green tells us.

“Records have tumbled at such a pace that, at one point, Bonhams broke the world record for a bottle of whisky at auction twice in the same sale,” in Hong Kong in May 2018—both of them also Macallans from 1926.

Partly in response to these very high prices, “the recently published 2020 Wealth Report by Knight Frank Luxury Index shows that whisky had risen in value by 564% in the past decade,” Green notes. And the million-dollar bottles of Macallan “need to be seen in perspective,” he opines. “They are the exception, not the rule. That said, there is plenty of hard evidence that the most desirable whiskies from the most sought-after distilleries have enjoyed strong growth in value at auction over the past ten years or so.”

There are a number of reasons for this. “As the Knight Frank report suggests, whisky, together with other luxury products, has become attractive as a potential investment while other areas have lost their appeal,” Green points out. “There are, however, other factors at work which are arguably of greater longer term significance.” Chief among them, the burgeoning number of whisky collectors worldwide.

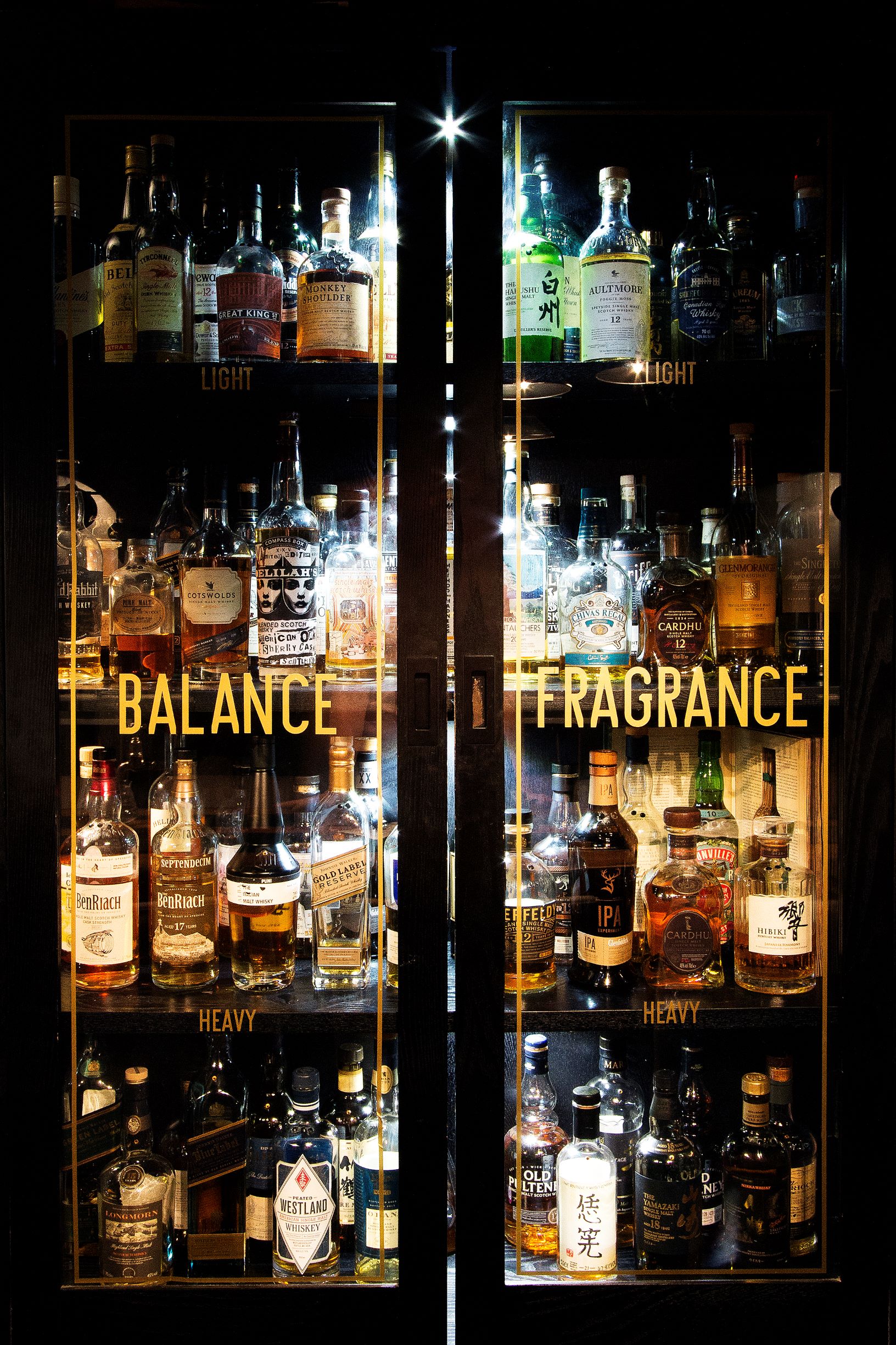

“When I started in auctioneering 20 years ago, whisky was offered as a discrete, and usually modest, section of wine sales,” Green says. “Today Bonhams runs four whisky sales in Edinburgh alone, and four more in Hong Kong. There are now collectors all over the world; not just in the traditional regions of Europe and the U.S., but also notably in the Far East,” as well as China and Japan.

Frank Coleman, Senior Advisor to the CEO of the influential Distilled Spirits Council of the United States (DISCUS), and one of the whiskey world’s most well-liked and respected figures, tells us that the ranks of whiskey collectors are being bolstered by “investors who now treat many rare bottles as financial assets,” noting that “there are syndicates, hedge funds, and high-net-worth investors in the game now.”

His advice is to focus on “collecting bottles from distilleries that are no longer in existence,” in addition to limited editions and vintages that are in extremely short supply. “For example, back in the late ’80s or early ’90s [under the name United Distillers] Diageo—now the world’s largest Scotch producer with 28 distilleries in Scotland and more on the way—began to issue the Rare Malts series, partly focused on leftover inventory from famous distilleries that they owned but had closed or repurposed, such as Rosebank and Port Ellen.”

When Coleman first became interested in collecting spirits 20-odd years ago, “some of those bottles sold for around $100 or less.” Now many of them “sell for thousands of dollars, far outstripping the sizable gains in the stock markets.”

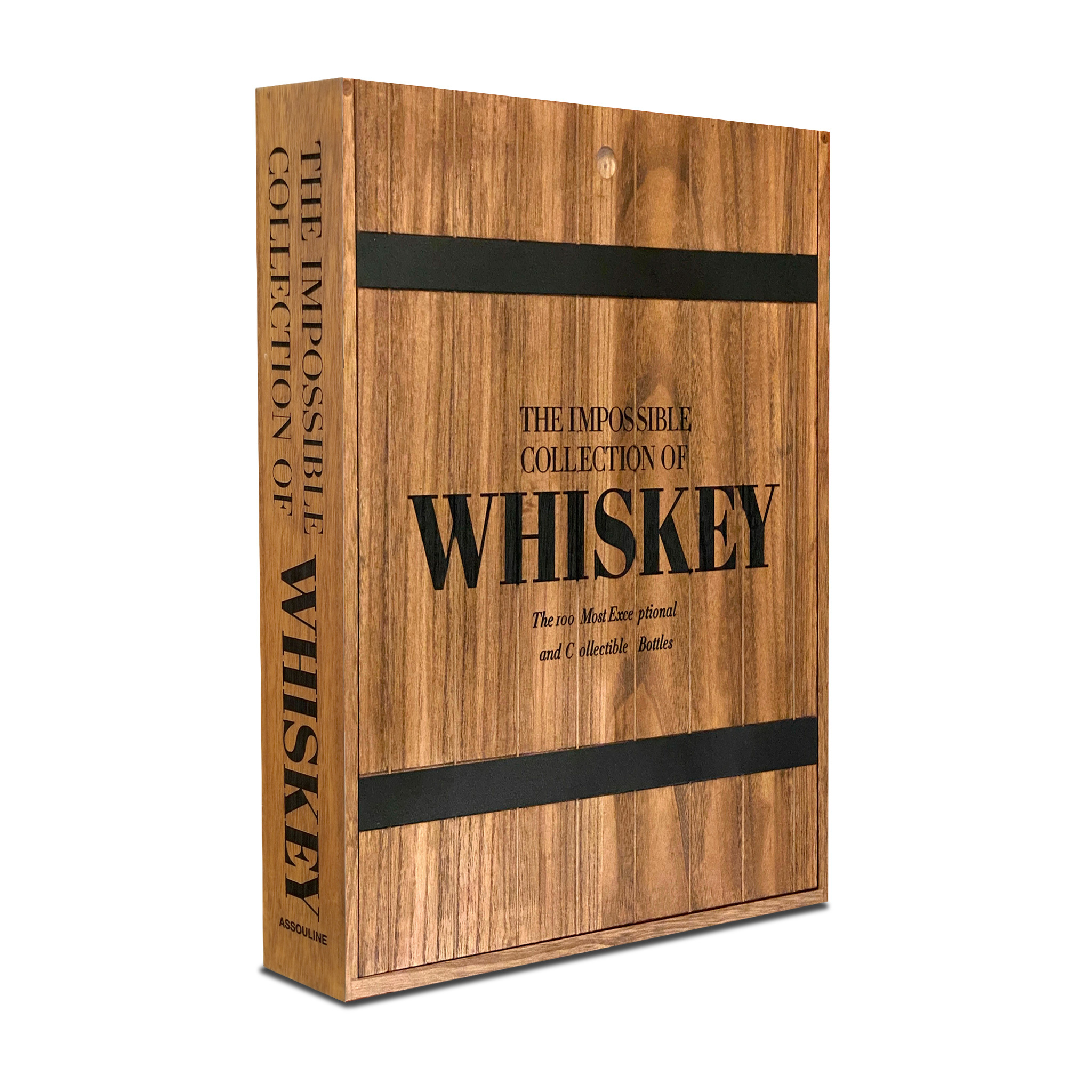

All of which makes this the perfect time to publish the definitive book on whisky collecting—or whiskey, as you prefer. While “whisky” usually connotes spirit distilled in Scotland, it also appears on bottles from the likes of Japan, India and Australia, while “whiskey” is found on most (but not all) labels originating in America and other locales.

The Impossible Collection of Whiskey covers all of them. For the gorgeously-illustrated new book from French luxury imprint Assouline, being published in a limited edition in a handcrafted wooden box and priced at $995, author Clay Risen selected 100 of the “most exceptional and collectable” bottles in the world.

In addition to seven-figure Macallans, Risen scoured the globe for rare whiskies distilled everywhere from the backwoods of Kentucky to the prefectures of Japan and all points in between.

“Here are whiskeys selected not only for their exquisite flavor but also for rarity, age, flavor, and innovation,” Assouline notes. “Bottles from countries with nascent whiskey markets, such as India and the Czech Republic, sit beside old American classics like Pappy Van Winkle and some of the rarest, most coveted bottles on the market,” such as Midleton Very Rare 45 Year Old, the oldest, most expensive Irish whiskey in the world, and Blanton’s bourbon’s rare Gold Edition.

The premise of the book is that, “Together, these 100 bottles comprise a collection of whiskeys so exclusive that no one could ever assemble them all under one roof ”—though in point of fact, a determined, patient and extremely rich collector might just be able to pull it off.

So where should the aspiring collector start? Try getting your hands on a bottle of the recently-released Yamazaki 55-Year-Old, which contains spirit from the 1960s, making it the oldest expression in the history of Japanese whisky. Only 100 were created, priced at about $27,000 apiece, and sold via a lottery open only to Japanese residents this past summer.

When one of them does surface at auction, expect the price to have doubled at least. As with any luxury product, when it comes to collecting, “quality, scarcity and exclusivity are key,” Bonhams’ Green says. True rarities like the Yamazaki 55 don’t appear very often, but “most leading distillers produce special limited editions of their very finest whisky,” which become instant collectors’ items, he notes.

“This might involve collaborating with another premium brand,” as Macallan has done very successfully with famed French crystal and glassmaker Lalique, which handcrafts custom decanters for some of the iconic distillery’s rarest offerings.

Somewhat more accessible, but in the same vein, is the coveted Woodford Reserve Baccarat Edition. Billed as “the world’s finest bourbon, aged to perfection in hand-selected XO cognac casks at the historic Woodford Reserve Distillery in Versailles, Kentucky,” it comes in a bespoke Baccarat crystal bottle with a special presentation box including a Baccarat crystal stopper. A limited quantity of the highly-collectable tipple will be available this holiday season at $2,000 per bottle.

“Our Baccarat offering is uniquely special because it combines the renowned traditions of classic French elegance and American spirit,” Chris Morris, Woodford Reserve’s Master Distiller, tells us. “It also helps us tell our story of Kentucky’s connection to France, with Bourbon County being named after the French Bourbon family, down to the town where our distillery is located in Versailles, Kentucky. The Baccarat Edition brings together the world’s finest bourbon and the world’s finest crystal, with both representing craftsmanship at the highest level.”

The Woodford Reserve Baccarat Edition deserves a place on the world-class collector’s shelf, next to Glenfiddich 50 Year Old, the oldest whisky Mr. Risen has ever sampled, worth $38,000 a bottle in 2010 and considerably more now. “The value of a whiskey this old is measured by much more than how it plays on the tongue,” Risen writes.

“The difference—the value added, so to speak—that age introduces is the amount of work that goes into it. It’s hard enough to make a decent 12-year-old whiskey; it takes genius-level craftsmanship to concoct something over a half-century.” And he points out, it’s a “collective genius.”

“A whiskey this old and this good is rarely the result of one person’s efforts, or even one team’s,” Risen writes. “It takes generations of care, skill and knowledge that is passed down; it is the expression of a well-honed, carefully-guarded distillery culture that extends from the master blender to the groundskeepers.”

Just ask Adam Hannett, Head Distiller of Bruichladdich, the small, entrepreneurial distillery on the remote Hebridean island of Islay dedicated to the preservation of traditional hand-distilling methods, a cult favorite among single malt enthusiasts. Originally built in 1881 and later shuttered for several years, it was revived in 2001 by a group of passionate private investors and whisky enthusiasts, prior to being acquired by the Rémy Cointreau Group in 2012. “In my opinion as a whisky maker, the thing that should make a whisky worth collecting is an appreciation of the incredible history and heritage, the story and the places that whisky represents,” Hannett says.

To him, “the wonderful thing about whisky is that it is the culmination of the hard work and expertise,” he tells us, “of the farmers who raise a crop, of the incredible skill and knowledge of the maltsters, the craft of the distillers to produce a spirit that represents the land, the place and the personality of the people, the craft of the coopers who raise the casks, and the blenders who patiently wait until they decide the time has come to place the amazing liquid into a bottle.”

When all is said and done he opines, “I think what makes a liquid collectible is not how few bottles there are, but how rare the spirit is.” The rarest Bruichladdich malts, with vintages dating back 50 years or more, sell for several thousand dollars, and are likely to fetch exponentially more in the decades to come.

Which brings up “the paradox of collecting,” as Risen puts it: “Whiskey is meant to be consumed—but how can you justify consuming something you’ve spent hundreds, even thousands of dollars to buy? Carefully tended, whiskey won’t go bad, though like a car driving off a lot, a bottle, once it’s opened, loses a good slice of its dollar value. Yet once opened, a whiskey bottle actually increases in value, in a different way—because now there is nothing to stop you from sharing it, and, ultimately, enjoying it.”

Because, as he so eloquently puts it, “Great whiskey is meant to be desired, envied, hunted and collected, but never hoarded. It is, above all, meant to be celebrated and shared.”

This article originally appeared in the Sept/Oct 2020 issue of Maxim