America’s Greatest Heroes Are Making the Most Twisted Zombie Film of All Time

Exclusive: We visit the set of the raunchy, blood-splattered, politically incorrect apocalyptic comedy ‘Range 15.’

Hollywood types are fond of comparing the grueling undertaking of producing a blockbuster film to going to war. Spike Lee, Warren Beatty, Steven Spielberg, and Francis Ford Coppola have all reached for martial metaphors to describe their efforts, despite the fact that none have ever been in combat. Naturally, those who have tend to disagree. Among them are first-time filmmakers Nick Palmisciano, Mat Best, and Jarred Taylor, who’ve all deployed to war zones but, until a week ago, never spent a single day on a movie set.

Now they’re attempting to shoot their own feature in three weeks flat.

“The main difference is this: Hollywood is a whole lot of narcissists out for themselves, loosely held together by people who are good at controlling narcissists,” says Palmisciano, a former U.S. Army infantry officer. “But when soldiers go to war, the primary mission is to take care of each other no matter how bad the situation is, and to get through it together. With that approach, we can do what Hollywood does. We can do anything. We’re unstoppable.”

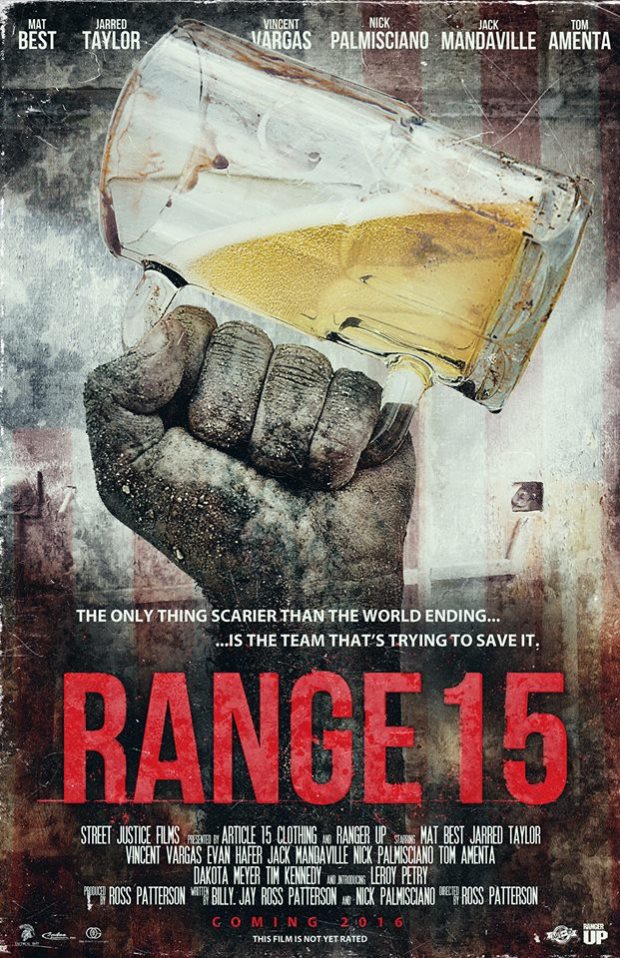

It’s a muggy Southern California morning in October, and Palmisciano, Best, and Taylor are studying line notes over a breakfast of scrambled eggs and coffee. Randy Newman’s “I Love L.A.” plays on repeat from Taylor’s iPhone. The location is an abandoned college campus in Pomona, two hours east of Los Angeles, which has been transformed into a zombie-infested war zone—the setting for a raunchy, blood-splattered, politically incorrect apocalyptic comedy called Range 15. Directed by indie oddball Ross Patterson (Helen Keller vs. Nightwolves), it’s the story of a group of war buddies who wake up in a drunk tank after a wild night of partying only to discover that the zombie apocalypse has begun and it’s up to them to save the world.

Aside from a few big-name cameos, the actors aren’t carrying SAG cards. Or not yet, anyway. Instead, they’re combat veterans, many of them highly decorated. What LeBron James and Michael Jordan are to basketball, these guys are to waging war. They’re the all-American heroes young soldiers aspire to be. Leroy Petry, a Medal of Honor recipient, plays himself in the film. So does Clinton Romesha, who also earned the Medal of Honor in Afghanistan. Along with Palmisciano, Best, and Taylor, they’re joined by Marcus Luttrell (the retired Navy SEAL played by Mark Wahlberg in Lone Survivor) and Tim Kennedy, a Green Beret who now fights in the UFC. Veterans account for about 90 percent of the cast and most of the crew, and together they represent the U.S. military’s best and brightest.

But you wouldn’t guess it from watching this scene. After breakfast, the actors make their way into a forested part of the campus, where they’re slathered in fake blood and equipped for combat. Petry and Romesha are up first. Armed with matching M4 carbines, the two men take their places in a small clearing and begin scanning the vegetation like soldiers on patrol. “You good to go, Leroy?” Patterson asks. Petry, who is soft-spoken in a hard-boiled, Clint Eastwood kind of way, flashes a grin and nods. Nobody told him about this scene until a few days ago.

Patterson calls action, and a grenade soars through the air and lands between the soldiers with a thud. Petry lunges for it. So does Romesha. Two war heroes, one grenade—that’s the setup for an elaborate and highly irreverent joke that military insiders will find amusing and few, if any, civilians will even register. Bickering ensues as each man insists on being the one who risks his life for the other. By the time Petry shoves Romesha out of the way and scoops up the grenade, it’s too late. The pyro explodes, and Petry’s left hand is quickly replaced by a blood-spewing prosthetic nub.

Here’s the funny part, or maybe it’s not funny at all: The scene is actually a satirical reenactment of a 2008 incident in eastern Afghanistan, when Petry grabbed an enemy grenade and tossed it away, saving the lives of his fellow Rangers and sacrificing his right hand in the bargain. “I sat up and I grabbed [the stump],” he told a U.S. Army reporter in 2011, just after President Obama awarded him the Medal of Honor for his act of heroism. “And it’s a little strange, but this is what was in my mind: ‘Why isn’t this thing spraying off into the wind like in Hollywood?’

“Back in character now, Petry clutches the fake nub on his left hand with the actual bionic prosthesis he now wears on his right. “Oh, no!” he cries. “Not again!”

Cut to Romesha. “Who has two thumbs and thinks that’s hilarious?” he says, laughing. “This guy!”

The blood is bright red and copious. It sprays into the wind like a fire hose.

“We can do what Hollywood does,” says Nick Palmisciano of his apocalyptic zombie comedy. “We can do anything. We’re unstoppable.”

A

bare-bones indie production shot with a budget somewhere south of $2 million, Range 15 is at once a

labor of love, an elaborate group therapy exercise, and, to a lesser extent, a marketing campaign for a pair of military-oriented apparel brands launched by veterans in recent

years, Ranger Up and Article 15.

But most of all, it’s a lark, a crazy escapade

launched with a YouTube-inspired DIY grandiosity and fueled by passion, camaraderie, strategic naïveté, and a go-for-broke spirit common to guys who’ve put everything they had on the line and lived to tell the tale.

The mission is to make a film that is the direct antithesis of every Hollywood war movie ever made. Or as Palmisciano likes to put it: to make a movie “so hardcore military, it makes Hollywood wet itself and run crying to Mommy.”

In other words, it’s an uncompromisingly in-your-face showcase of the filmmakers’ most perverse apocalyptic fantasies. And not surprisingly, given what they’ve lived through, these guys’ apocalyptic fantasies make a Michael Bay production look like an exercise in sober restraint. One character will get his genitals bitten off by a zombie. Another will fall in love with, and eventually marry, a blowup doll. Luttrell will get torn limb-from-limb, and someone will shrug his shoulders and say, “Looks like we’re the lone survivors now.”

“After watching these guys try to save the world,” Palmisciano says, “you’ll never thank another veteran for their service ever again.”

Hollywood’s love affair with veterans began in earnest in the immediate aftermath of the Vietnam War. Until that point, pop culture representations of soldiers were typically thin, jingoistic, and largely confined to the battlefield. It wasn’t until films like The Deer Hunter and Apocalypse Now came along in the late ’70s that the primary focus shifted from the battlefield exploits of brave Americans to the psychological ramifications of those exploits. In a few short years, veterans went from being indestructible heroes to damaged goods, tarred by the horrors of combat. And that “veteran as victim” narrative has persisted through the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Of course, these war films have generally reflected a Hollywood sensibility and the strong antiwar sentiment that went along with it. Screenwriter Deric Washburn didn’t interview a single Vietnam veteran to write the script for The Deer Hunter. But it didn’t matter: The film won five Oscars, including best picture, at the 1979 Academy Awards, while best-screenplay honors went to Coming Home, another movie about battle-scarred Vietnam veterans, which starred antiwar activist Jane Fonda. That’s not to say veterans haven’t made their mark in Hollywood. Actor Audie Murphy was a Medal of Honor recipient, and director Oliver Stone earned a Purple Heart in Vietnam. But Palmisciano, Best, and Taylor aren’t in the business of making blockbuster films or Oscar bait. “We want to make the movie the military has always wanted,” says Palmisciano. “We want to make the movie the military deserves.”

If the general moviegoing public wants to flock to Range 15, so much the better.

Back in 2006, with military-inspired looks (epaulets, cargo pants, khaki, and camo) marching down high-fashion runways, actual “military apparel,” the kind military guys might wear, was pretty much whatever you could scrounge up at the local Army Navy surplus store. “It was all just Vietnam-era biker stuff,” Palmisciano says. “I wanted to make something that was really for us, not a caricature of us.” Fresh out of the army, he hired a team of veterans and got to work launching his own clothing line. Dubbing the company Ranger Up Military Apparel, he set out to create a brand that would be for war fighters what PacSun was for surfers or Fox Racing for motocross racers. Soon, shirts emblazoned with phrases like ‘I am a product of harsh necessity’ and ‘You’ll have a blast at Baghdad summer camp’ were ubiquitous on U.S. military installations around the world.

To increase visibility, Palmisciano started making YouTube videos. One of the first productions was a satirical workout video featuring himself and his team sporting tiny shorts and codpieces. To date, it’s been viewed more than 400,000 times.

Meanwhile, in Texas, Jarred Taylor, an active-duty airman with Hollywood aspirations, was putting together his own A-team of enterprising veterans. Like Palmisciano, Taylor realized there was a demand for media that catered exclusively to a service demographic. He also saw the military as an enormous untapped pool of quality talent—guys who were good-looking and confident enough to be on camera but who also possessed more admirable qualities. “It’s guys like the ones I served with in Iraq that your kids should be following on Twitter,” he says. “Not Kim Kardashian. I wanted to make that happen.”

To do so, Taylor would need someone with star potential. And he found just the guy on YouTube: a young ex–Army Ranger from Santa Barbara named Mat Best. Tall and broad-shouldered, with an array of expensive tattoos down his brawny arms, Best was the avatar of military cool, with a small but fiercely loyal following.

Between contractor gigs overseas, Best began making trips to El Paso, where Taylor was stationed with the Air Force. “He’d fly in for a few days and we’d shoot a bunch of stuff,” says Taylor, “and then he’d go back to Afghanistan or Pakistan or wherever he was working at the time.” To raise money for more high-end productions, Best and Taylor decided to start their own military apparel company, inspired by Ranger Up. The line, called Article 15, was an instant hit. As the money rolled in, Best’s YouTube following exploded.

“The first one I saw was the one where Best is making fun of the SEALs,” Luttrell recalls. “My teammates and I were laughing our tails off.”

The mission is “to make a movie so hardcore military it makes Hollywood wet itself and run crying to mommy.”

The idea for the feature, Range 15, originated with the Article 15 camp. “We knew we’d be way more successful if we partnered with Ranger Up,” Best says of teaming with a competitor. “And that’s the military ethos we sought to promote with this film: We’re stronger together than as individuals.”

“I read the rough draft for the script and thought that with a little work we’d really have a winner,” Palmisciano says. “I just wanted to make sure it accurately reflected the military.” Patterson helped polish the script written by scribe Billy Jay with help from the Article 15 guys, and signed on as director. They launched an Indiegogo campaign to raise a modest $325,000 budget. By day 60, contributions topped $1 million, making Range 15 the fourth-largest crowd- sourced movie ever.

Palmisciano, Best, and Taylor signed on to play exaggerated versions of themselves, and other Ranger Up and Article 15 employees took roles as well. The cast was soon rounded out with just about every high-profile veteran the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have produced, and dozens more volunteered as everything from stunt doubles to bus drivers. Meanwhile, Kennedy, the UFC fighter sponsored by Ranger Up, rallied his fellow competitors to play zombies. And eventually, big-name celebs like William Shatner, Sean Astin, and Danny Trejo also signed on, generously agreeing to work for reduced rates.

Fortunately, there are a lot of people who want Range 15 to succeed. On day seven, the film’s biggest and most expensive prop, a 21⁄2- ton M35 cargo truck (or “deuce and a half”), ran out of juice. Filming would have to be delayed for three days until a set of military-grade jumper cables arrived by FedEx. Instead, Palmisciano posted an SOS on Facebook. Within two hours, a group of marines arrived on set with a pair of cables they had smuggled off their base more than 100 miles away. “I’m not going to say their names because they could get in trouble,” Palmisciano says. “But they saved our asses.”

The nascent filmmakers are clearly in over their heads, but they seem to relish the pressure. They know the difficulty soldiers face when their primary mission is over—the struggle to fill that gap and find a real purpose, something formidable. “Look around you,” says Palmisciano. “Everyone here is working their fucking asses off. One of the biggest dangers I see with veterans is that they work hard as fuck in the military and then they expect to just get handed a good job when they get out.”

Best could easily have been one of those guys. During his four years as an Army Ranger, he completed five combat deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan, before taking jobs in various conflict zones as a contractor for the CIA. By the time he turned 28, he had spent nearly half his adult life on the battlefield. Nobody would’ve blamed him had he just retired to the beach and spent the rest of his days drinking Bud Light and telling war stories. But Best had other ideas.

“It’s important to show the younger guys that our service doesn’t have to end at the military,” he says. “You can go on to do something bigger but also maintain where you came from.”

Best now co-owns two companies in addition to Article 15, though he’s better known as the YouTube guy. His videos are shared religiously among the guys I served with in Iraq and Afghanistan. Every time I open Facebook, there’s another one: “Epic Rap Battle: Special Forces vs. MARSOC,” “You Might Be a Veteran If…,” “GUNS ARE BAD! Logic from a Hipster.”

Back on the set, Kennedy stands, half-naked and covered in blood, in the center of a boxing ring. He’s wearing a pair of skin-

colored briefs sprouting a bushel of artificial pubic hair and holding up a severed head be- fore a cheering crowd. As the applause grows increasingly frenzied, he punts the head over the crowd like a football. Behind him, a guy throws up his arms and yells, “It’s good!”

Palmisciano likes to say that Range 15 is what you’d expect from combat veterans if you actu- ally knew any combat veterans. “In Hollywood, it’s either we’re glorified heroes or totally broken with post-traumatic stress,” he says. “That’s a problem. If you constantly tell people they should act like emotionless, two-dimensional creatures, or that they are damaged, they’re going to start believing it.” With unemployment and suicide rates among veterans startlingly high, Range 15 is an attempt at creating an entirely new post-military narrative, shedding the aura of tragedy in favor of a fired-up, gung-ho spirit steeped in black humor. The same stuff that helps a soldier survive, say, a year in the Korengal Valley can be channeled to achieve success and happiness in the civilian world, or so the thinking goes.

http://bcove.me/nulau6du” tml-render-layout=”inline” tml-embed-thumbnail=”http://brightcove.vo.llnwd.net/v1/unsecured/media/1782619960001/201603/750/1782619960001_4790164685001_Screen-Shot-2016-03-07-at-1-08-32-PM.jpg?pubId=1782619960001

But really, the film is an excuse for a bunch of people whose lives have been consumed by their war experiences to cut loose. “Being a war hero is both an incredible honor and a curse,” says Palmisciano. “You earn the Medal of Honor, and now people who haven’t done what you’ve done feel like it’s their right to impose standards on you. It’s like Leroy and Clint are in this prison where they have to be Boy Scouts all the time.

“Think about Marcus Luttrell,” he continues. “He’s constantly asked to relive the worst day of his life and talk about what he learned from it. That sucks. But in Range 15, they’re al- lowed to be funny and they’re allowed to be themselves. We’re making the jokes that no one else would make, because it’s fucked up and it violates all conventions of respectable behavior. But that’s military humor. These guys aren’t victims; they’re tough fucking dudes. That’s how they want to be treated.”

After Kennedy’s head-punting scene, everyone migrates to a nearby dirt field for yet another epic battle. While the opposing armies prepare for combat, I spot a woman with electric-purple hair and no arms. Two rubber daggers protrude from a pair of stumps that terminate inches above where her elbows used to be. Patterson yells “Action!” and the armies clash. The woman sprints into the fray, leaps onto a zombie’s back, and drills the daggers into its flesh.

This is Mary Dague. Later, she tells me that eight years ago, she was working as an army bomb tech in Baghdad when both her arms were blown off by an IED. The shirt she’s wearing is one of Ranger Up’s more popular designs: It has a picture of a tyrannosaur with tiny arms dropping a grenade above the words ‘t-rex hates hand grenades.’ She’s one of about a dozen veterans who lost limbs in Iraq and Afghanistan who appear in the film.

“There’s a scene in the movie where someone tosses me car keys and I can’t catch them,” Dague says. “Stuff like that actually happens to me quite frequently, and I find that making light of it helps. I certainly don’t want people to pity me.”

That night the principal cast convenes at the outdoor bar at the Chateau Marmont. The next day

will be their first off in nearly three weeks. The mood is light and a little reckless. Shots are poured. War stories are told. Jack Mandaville, a Ranger Up employee who was a terrified 18-year-old marine during the 2003 invasion of Iraq, is celebrating with a 12-pack of Coors Light. (He plays a bumbling half-wit in the movie—a role that required him to carry a blowup doll for the duration of filming.) But it’s not until Palmisciano, who wrestled at West Point, starts grappling with one of the camera guys that I realize we’re all completely drunk.

“Where’s Mat?” someone asks. Everyone stops what they’re doing to look around; Best has disappeared. “He probably went to sleep,” figures Palmisciano. The horseplay resumes. An hour later, Best resurfaces. There’s a bottle of whiskey in his hand. His eyes are glassy. Judging by the cheers that accompany his return, I suspect he’s usually the life of the party. “I’m going to bed,” he says. Everyone moans.

“Where have you been?” I ask him. Best lets out a long sigh and holds up the bottle. “I’ve just been walking, that’s all,” he says. “Sometimes when you’re dealing with shit, you just gotta deal with it on your own.” With that, he turns and leaves again.

Watching him go, I can’t help thinking of this meme that often pops up on my Facebook feed. The image varies, but it’s always a photo of soldiers in either Iraq or Afghanistan. They’re covered in filth and exhausted-looking, and usually they’re in the middle of a really intense fire- fight. It says, PTSD: The Moment You Realize You’ll Never Be This Awesome Again. It’s a joke, of course, but there is some truth to it. For many veterans, the real struggle doesn’t begin until they’re 10,000 miles from the battlefield and normal life resumes.

For Best, Palmisciano, Taylor, and the dozens of veterans who flew in from as far as Fort Richardson, Alaska, to make this movie, the last three weeks were an opportunity to be “awesome again,” to experience the thrill, responsibility, and camaraderie of being a soldier once more. Now everyone is headed home, where the straightforward mission of shooting a film will give way to the myriad stressors of everything else.

But not for long. They’re already planning a sequel.

Range 15 hits the festival circuit in May.