Meet the Mail-Order Mercenaries of ‘Soldier of Fortune’ Magazine

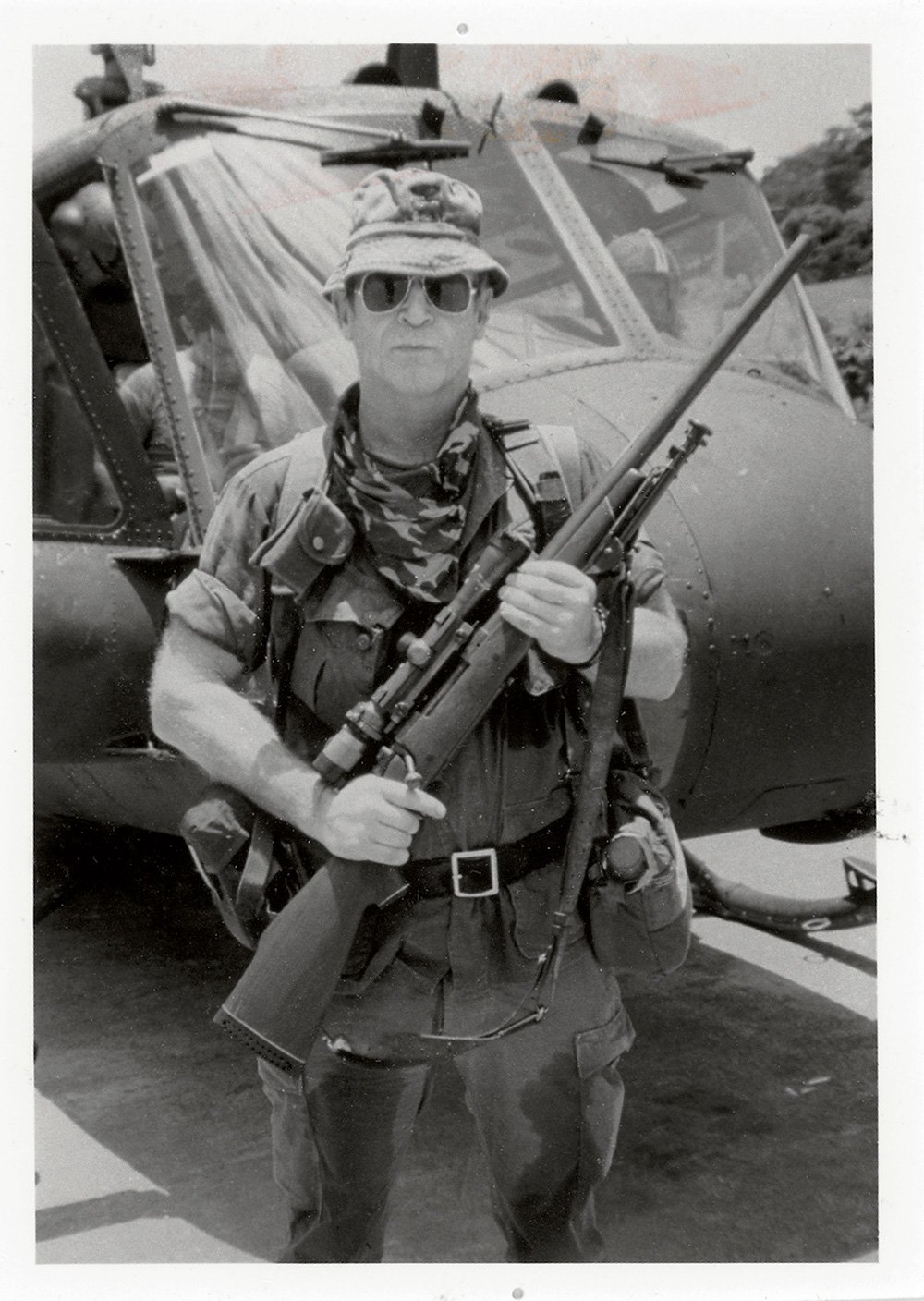

Lieutenant Colonel Robert K. Brown and his infamous “Soldier of Fortune” have long had the Second Amendment in sight.

After missing his 23rd straight shot, Lieutenant Colonel Robert K. Brown is ready to call it a day.

“Fuck me—I’ve had enough,” the founder of Soldier of Fortune magazine growls as he puts his brand-new Ruger Precision Rifle down on the table. “I definitely didn’t win any prizes today.” Brown has been aiming for a 6-by-10-foot painted metal silhouette of a white buffalo 1,123 yards away—a distance greater than the length of 11 football fields—but keeps circling around the target as the wind shifts.

As he adjusts the brim of his red-and-black Soldier of Fortune baseball cap forward on his bald head and gets to his feet, he turns to the motley crew of about a dozen old Army buddies, ex-CIA spooks, magazine contributors, and a few fans who have joined him for a weekend of shooting at the Whittington Center, a National Rifle Association–owned gun range in northern New Mexico where Brown serves as a trustee.

“Anyone else want to try this?”

One by one, members of the group take turns aiming at the white buffalo, almost all of them hitting the target in the first few shots.

“Hey, Bob, you’re the only trustee who hasn’t hit it yet,” one of his pals jokes.

“Any other comments, gentlemen?” Brown says.

“You want polite ones?”

“Just keep it to yourself, then.”

At 83 years old, the colonel seems like a feisty grandfather at first, wearing Ambervision glasses, temporary braces on both knees, white socks pulled halfway up his calves, and hearing aids from years of being around loud, high-powered weaponry. But he is not a man to be messed with. By his count, he has seen action in more than a dozen conflicts around the world and been shot at more times than he can remember. With a pistol strapped to his belt whose custom grip is emblazoned with a U.S. flag and a bald eagle, Brown continues to work full-time

“Boulder is 25 square miles of hippy-dippy bullshit surrounded by reality. I come down here to cleanse my soul,” Brown tells me, the words coming out of his mouth in bursts like machine-gun fire. “You know what they say about the golden years? It’s bullshit.”

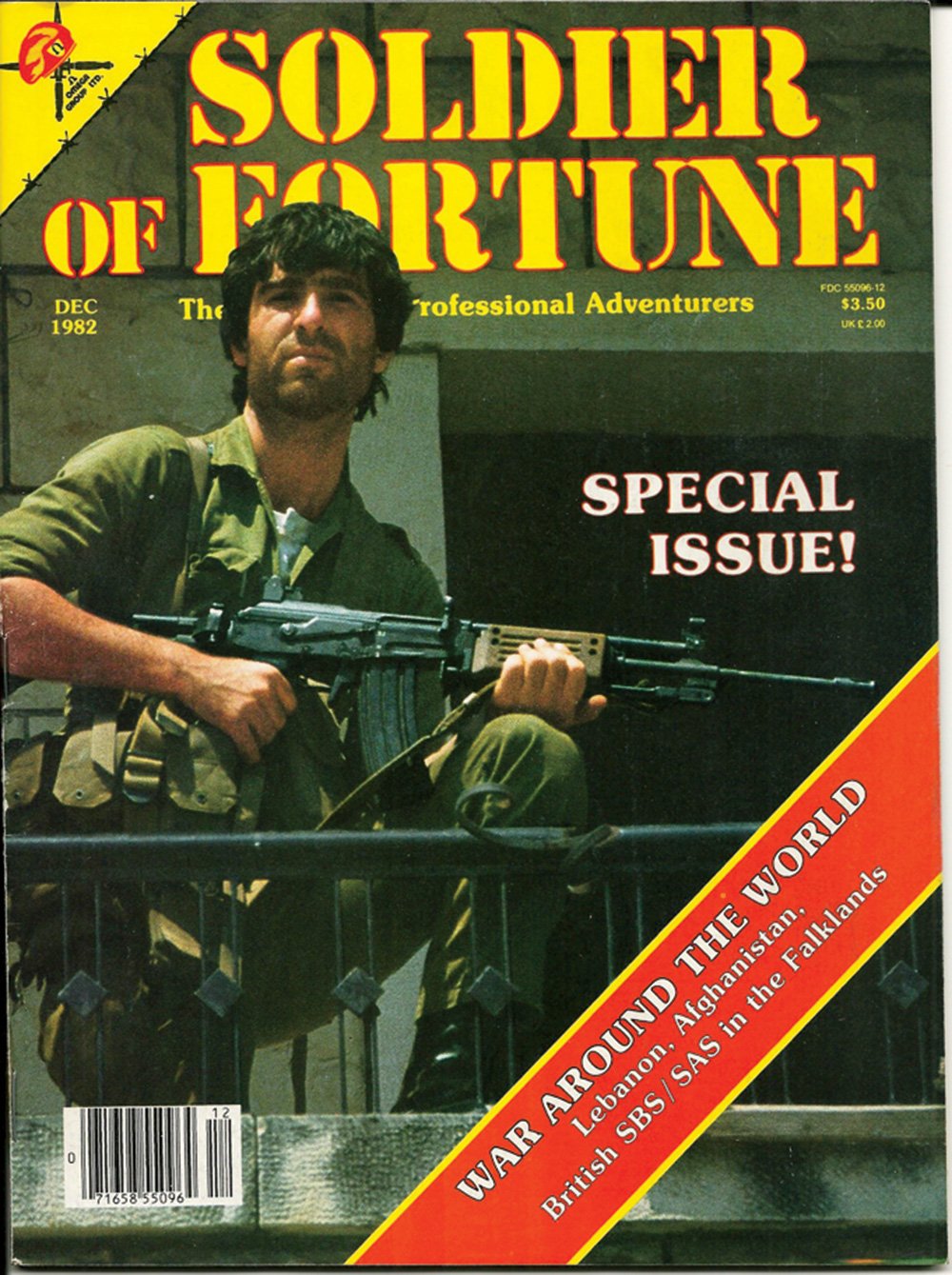

Dubbed “the Journal of Professional Adventurers,” Soldier of Fortune has, since 1975, chronicled a shifting, no-holds-barred world of black ops and mercenaries fighting Communism and terrorism. Its reporters have operated unlike most, carrying guns along with their pens and cameras, writing first-person accounts from battlefields around the world in what Brown likes to call “hardcore participatory journalism.”

“We would create the story, gin up a lot of action, and then write about it for the glistening pages of our bad-boy magazine,” is how he de- scribed it in his 2013 memoir, I Am Soldier of Fortune: Dancing with Devils.

In many cases, its writers really were mercenaries, and six Soldier of Fortune correspondents have been killed in action over the years, in places like Angola, Nicaragua, Burma (now Myanmar), and Sierra Leone (where legend has it that the remains of reporter Robert C. MacKenzie were eaten by rebel fighters).

The small weekend gathering at Whittington has effectively replaced the annual Soldier of Fortune conventions Brown held for two decades that used to draw hundreds of camouflage-clad war buffs to the desert for displays of military firepower, weapons, tactical training, and apparently quite a lot of drinking. Brown says the showcase demanded more manpower than his downsized magazine could staff, so he pulled the plug a few years back in favor of just spending time with his close friends.

Several members of his entourage have traveled hundreds, even thousands of miles to join the colonel for the weekend. Some he has known since his days in Special Forces in Vietnam, and others he has met on a variety of battlefields along the way.

“The vast majority of the people I have been close to have had some involvement, in one way or another, with the magazine. Some of them have been with me in the shit, others I know be- cause they have written for us, and then there are guys I’ve met in fighting for gun rights,” he says. “They are an eclectic group.”

While many of them have also known each other for years, the linchpin of the get-together is undeniably the colonel—often referred to as RKB or Maximus by friends. His colorful personality commands attention and brings out a mixture of awe, respect, and genuine affection among the gang of pretty gruff guys.

Perhaps the oldest pal in the group is Robert Bernard, the Army medic who saved Brown’s life back in 1969 when he was seriously wounded in a mortar attack in the central high- lands of Vietnam. Known as “Bac si” to his buddies (which means “doctor” in Vietnamese), the soft-spoken Bernard still keeps a close eye on the colonel’s health.

“He hasn’t always taken the best care of himself, so somebody has to look after him,” the 77-year-old tells me. “He was the kind of guy you wanted as your CO in Vietnam—he really stuck his neck out for the people he was in charge of— and he is the kind of guy you want to have as your friend in life. Never a dull moment with him.”

For 40 years, Brown has served as an inspirational figure for a particular brand of misfit, whether they were fighting for a cause or a price or just seeking a bit of adventure in various hot spots around the world.

It was for guys like Bernard and his generation that Brown initially created Soldier of Fortune. When he launched the magazine, he had hoped to give something to the Vietnam vets who were coming home and finding themselves spat at and being called “baby killers” by antiwar peaceniks.

“A lot of Vietnam veterans felt they weren’t given their due, so I wanted to promote the concept of giving them recognition. We said our blood was just as red as anyone who fought in WWI or WWII or Korea, but that wasn’t the case in society at the time,” Brown says.

Later the readership expanded to include a broader swath of military buffs, hard-core cold warriors, and a fair share of young men who would later join the armed forces inspired by the blood-and-guts tales of patriotic derring-do they had read in its pages.

“It was reading Soldier of Fortune as a teenager that inspired me to join the Army. There are a lot of guys who will tell you that,” says Jerry Kraus, a 50-year-old insurance agent and Soldier of Fortune field editor from Colorado who has become the colonel’s right-hand man of sorts and drove down from Boulder with him for the weekend.

Brown says one of his most cherished mementos is a signed copy of Chris Kyle’s American Sniper, in which the marksman (who was killed in 2013) thanks Brown in the dedication for in- spiring him to join the military.

But the troubles faced by print publishers as readers increasingly move online, plus the question of how to keep a magazine relevant that was born in the days of the Cold War and is geared largely toward men who have long been collecting social security, have begun to weigh on Brown.

“Obviously we are nowhere near where we were during our heyday in the 1980s, but we bring in a little coin and cover costs,” he says. Still, Brown now finds himself having to do much more of the work, as he is down to just an associate, two part-time editors, and a contract art director from a peak of about 50 employees in the early 1980s.

That has made it hard for him to get out into the world and do what he loves to do most—fight. “You know, I just don’t have the time. We used to have a lot of people running the place. It’s hard to do all this with just a few people and still have the time to get out there. I may try to go to Ukraine or Kurdistan soon. I still have good contacts in both places,” he says.

Despite the fundamental role Soldier of Fortune has played in his life (“it’s as much an extension of me as Playboy is for the guy who walks around in his pajamas all the time”), Brown says he has been negotiating to either bring in younger partners or even sell the magazine altogether.

For 40 years, Brown has served as an inspirational figure for a particular brand of misfit, whether they were fighting for a cause or a price or just seeking a bit of adventure in various hot spots around the world. But as time passed and the world changed, the colonel is the first to admit that the magazine’s hard-charging ethos may not have the same impact today.

“Vietnam veterans have gotten older and settled down. Some have died. The Rambo era—whatever that amorphous phase was—is no longer. Who knows what it was, but there was something there. Of course, the Cold War is over and granted we have the War on Terror- ism, but it is not the same thing,” he says. “We never would be able to do now what we were able to do back then.”

In its early years, Soldier of Fortune regularly ran full-page recruitment ads for mercenaries willing to fight with the white supremacist government of Rhodesia against Communist-backed black guerrillas. That led some members of Congress to call for the magazine to be investigated for possibly violating the Neutrality Act (the magazine was ultimately cleared of any wrongdoing).

Editorially, the magazine focused heavily on war stories and first-person dispatches, with correspondents jetting off to fight in and write about wars in the far corners of the globe. Issues in the 1970s featured regular reports on the situation in places like Rhodesia and Angola. As the 1980s rolled around, the focus moved to Central America’s bloody wars and the fight between the Mujahideen and the Soviet army in Afghanistan. In the 1990s, the focus became increasingly domestic, with an onslaught of pro–Second Amendment articles critical of the Clinton administration and its gun control efforts. The next decade the magazine turned to tales from the War on Terror and on efforts to control America’s borders.

While it is unflinchingly pro-military and pro-police, the magazine is also deeply suspicious of government overreach, which has also made it popular among antigovernment types (Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh was a subscriber).

The magazine continues to focus on similar themes, but battlefield articles are now less often written by the ragtag group of fighter-journalists that set the magazine apart years ago. The June issue had a long feature story on South African mercenaries (“mercs” in Soldier of Fortune lingo) who were going to Nigeria to fight the radical Islamist fighters of Boko Haram, but the piece was reprinted from a web- site that publishes academic articles. A first-person account of embedding with Kurdish Peshmerga fighters battling ISIS in Iraq was similarly reprinted from a conservative political website.

At its height, the magazine sold around 150,000 copies on newsstands each month (the biggest seller, at 182,000 copies, was the June 1985 issue, whose cover featured a shot of a shirtless Sylvester Stallone firing an M60 machine gun from the film Rambo: First Blood Part II ). Sales have varied widely over the years, usually seeing spikes when the U.S. got into a war. Brown says it was always difficult to have an ac- curate sense of how many people read the magazine, because a single copy might get passed around within an entire platoon. He declines to discuss the current circulation, and the magazine isn’t independently audited. He acknowledges being “technologically illiterate” but says he has been getting help improving Soldier of Fortune’s antiquated website and presence on social media.

“My lady friend is the one who has the better knowledge of what goes on on Facebook and the website. We had a lot of bad experiences with people helping us try to build the website, and all of them turned out to either be inferior or incompetent,” he says. “We have been growing online. On Facebook, we now have more than 850,000 likes.”

“The magazine is Bob, and Bob is the magazine. It would never be the same without him.”

Licensing has also proved lucrative over the years, with the magazine’s name being used for a successful video-game series, a short-lived television show, and a number of military-themed novels.

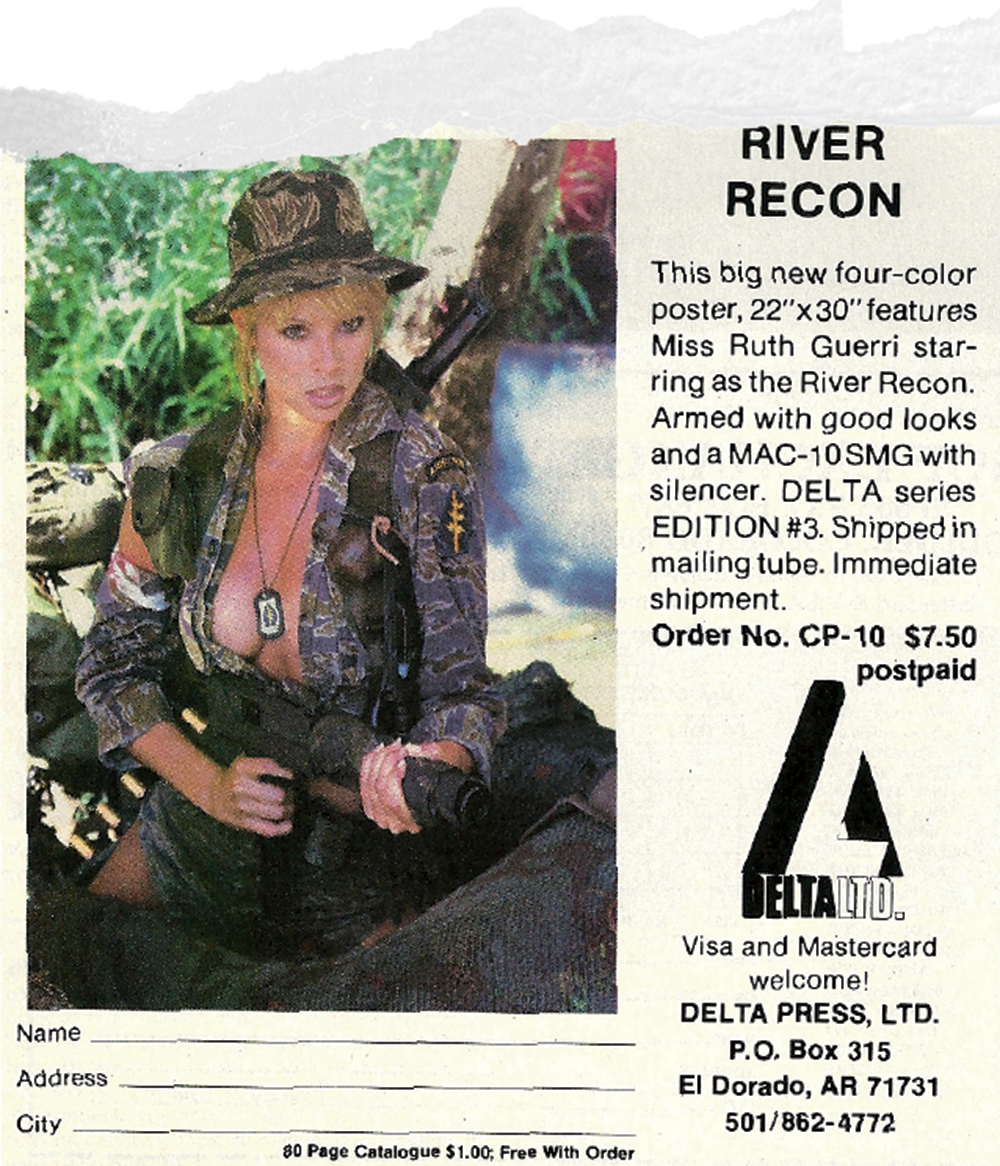

Perhaps the clearest change has been the advertising. At the beginning, Soldier of Fortune featured scores of classified listings for itinerant guns-for-hire. Ads like “Ex-Marine seeks employment as mercenary, full-time or job contract. Prefer South or Central America but all offers considered” were commonplace. In the 1980s and early ’90s, the magazine spent years battling several multimillion-dollar lawsuits brought by families of people targeted or killed by hit men who had been hired through its pages. All were either settled or had their huge jury awards overturned on appeal.

“They really tried the magazine, not the cases. Two guys meet through the magazine, they have a friendly relationship for six months, they don’t talk about anything illegal. But then six months later, they agree to commit this horrendous crime. Well, if they meet in a bar and six months later they say, ‘Let’s rob a bank,’ should the bartender be held liable? It was total crap,” he says.

Regardless, the magazine stopped taking those kinds of ads in 1985. But its classifieds continued to offer everything from throwing stars and nunchucks to posters of G. Gordon Liddy holding an Uzi. Ads now tend to be more like what one might expect in any gun magazine, marketing handguns, rifles, hunting apparel, and gun accessories. In the early 1980s, the magazine regularly topped 110 pages. By the mid-2000s, it had dropped to 82. In recent years, the number has dwindled to 64.

“This has never been just a moneymaking venture for me,” Brown says. “If it had been, I would have made a lot more.”

Over the years, the colonel routinely sank his largesse back into financing whatever mission the magazine had embarked on. He says he personally spent more than $300,000 backing efforts to hunt for POWs he and many of his readers believed had been left behind after the Vietnam War. “And that was 30 years ago,” he notes. The magazine regularly advertised big-ticket rewards to anyone willing to turn over proof that the Vietnamese had used chemical weapons or to Nicaraguan pilots ready to hand over an intact Soviet-built helicopter.

It also helped raise money for the Mujahideen fighters that years later morphed into the Taliban and helped give rise to Osama bin Laden and al Qaeda. Brown has said that based on the information he had at the time, he felt he had made the right decision.

Even if the magazine no longer has the cultural reach it once did, Brown’s friends worry about the colonel no longer being involved.

“The magazine is Bob, and Bob is the magazine. It would never be the same without him,” says Gordon Hutchinson, a firearms instructor and author from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, who has known the colonel for a decade. “We would never be the same without him. We can’t have that.”

After a long day of shooting long-range rifles, shotguns, semiautomatic weapons, and a Civil War–era, muzzle-loaded sniper rifle called “the heavy,” the colonel suggests the group drive 30 miles to Cimarron, New Mexico, to have dinner at the 144-year-old St. James Hotel. Steeped in Wild West history, the hotel was once a regular stop-off point for outlaws like Jesse James and lawman Wyatt Earp.

To those who don’t know him well, it’s easy to assume Brown is a posturing octogenarian who never outgrew an adolescent obsession with big toys that go boom. But as he holds court at the dining table, he reveals a more subtly charismatic side, flirting innocently with the waitress and hostess and commanding the attention of all those gathered around.

“Bob is one of those guys who, when he walks into a room, everyone kind of turns around. He’ll doff his cap to a lady. He’s almost European in his courtliness and manners, like a real officer and a gentleman,” Hutchinson says. “You don’t meet a ton of people like that.”

Brown is deeply conservative but says he generally doesn’t like talking politics, although when the topic of Republican front-runner Donald Trump comes up, he is quick to voice his opinion.

“Trump is a fucking nightmare, and I think it’ll be terrible if he slips in. I just fear he is going to pull a Ross Perot on us and run as a third-party candidate, which will just hand it to [Hillary] Clinton. That would give me a fucking stroke.”

In the 1990s, the magazine poured tons of ink into criticizing Bill Clinton, featuring a regular column called “Slick Willie Watch.”

At one point in the evening, the colonel pulls me aside to make sure I see the bullet holes that pock the tin ceiling of the restaurant’s saloon, the indelible marks of more than a few drunken Old West gun fights.

“Hard to find that kind of living history,” he says. “I don’t really drink anymore. Believe me, I’ve done enough drinking for a lifetime as it is.” Still, the colonel has made a point of leaving his sidearm in the car.

Brown tells me he has been married and has kids from whom he is estranged, but that he doesn’t want to talk about them. “I’m just not going there.”

When the colonel goes to pay his tab he discovers that it, along with the dinner bills of several of the old-timers in the group, has already been paid by Bruce Roberts, a fan of the magazine from North Dakota. A security guard for a gas facility with an uncanny resemblance to the country musician Charlie Daniels, Roberts never met Brown before this weekend but had hit it off with him when they corresponded over the purchase of a military history book from his collection.

“It’s just an honor to be around him. He’s really a legend. I read the magazine going back to when I was a teenager, and I feel like I know all these guys. It’s amazing to meet them,” he says.

After the party breaks up, Brown comes back to my car to retrieve his gun, as he plans to ride back with someone else. As he walks off, Brown puts his arm around the shoulders of Harry Claflin, a longtime pal who spent many years in the 1980s training government troops in El Salvador in their war against Communist rebels.

“Thanks, buddy, for coming out for a good time—there won’t be many more of these. You know, life’s a bitch and then you die.”

The next morning, Brown tries to get everyone together for a group photo before shooting a round of trap.

“It’s like fucking herding cats!” he yells as the group mills about.

Once everyone lines up with their shotguns, Brown suggests they hold up a shell in their free hand in a way that makes it look like they’re flipping the bird to the camera.

“That’s right. The Wild Bunch rides again,” he says, referring to the classic 1969 Western that is his favorite film.

Brown, who has sat on the NRA’s board of directors for three decades, then departs for a business meeting.

“You boys are on your own. Have fun shooting.”

Brown says he came up with the idea for the magazine while traveling in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) when it was under white-government rule and was enlisting mercenaries to fight black guerrilla forces.

He was told several of the fighters were headed to Oman after their tours to put down an insurrection. Out of curiosity, Brown wrote to Oman’s ministry of defense, which sent him a contract. Rather than sign up, Brown took out ads in gun magazines: “Want to be a mercenary in the Middle East? Send $5.” In return, he’d send the contract.

“I got scores of replies,” Brown says. “Newsweek spotted this and did an article on my ad, and it just went through the roof. I was getting replies from people in Bangladesh, Greece— ‘I was in the army in Turkey for five years; I want to be a mercenary.’ I realized I was onto something.”

With the money, Soldier of Fortune was born.

But it’s guys such as Claflin, who worked with the likes of Oliver North in helping fight against Communism in Central America, that have given rise to theories that the magazine’s origins might have been less organic.

In a 1984 article in Covert Action Information Bulletin, leftist firebrand writer Ward Churchill argued that Soldier of Fortune was actually an elaborate CIA front geared toward organizing private soldiers to fight the U.S.’s battles in the period after the Vietnam War, when committing American troops abroad was politically problematic. Churchill noted that for years before the magazine launched, Brown regularly found himself in the middle of situations where the CIA played a role. Churchill also pointed to the fact that many of the magazine’s writers had long been suspected of ties to the intelligence community. Brown has two words for Churchill’s theory: “Utter bullshit.”

What’s not bullshit is that the necessity for highly trained but underemployed soldiers to advertise their wares or otherwise beat the bushes to find gigs has declined in recent years as the process has become more corporatized. Governments and companies working in troubled parts of the world can now simply turn to big private security firms, like the company once known as Blackwater, which have rosters of such men at the ready. Additionally, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the market got flooded by scores of well-trained fighters with little to do. That, coupled with the magazine’s aging readership, has resulted in an audience that is perhaps more armchair quarterback than active combatant.

Brown has increasingly focused his energy in recent years on the struggle over gun rights, and the magazine has sometimes resembled more of an NRA soapbox than a pure military review. Yet he still tells friends that he has plenty of fight left in him.

“When I last saw the colonel, he told me, ‘You know, I think I still have one more good war in me,’ ” Hutchinson recalls. “I just looked at him and said, ‘Bob, are you crazy? You’ve been in every skirmish, large and small—including some really stupid ones—going back to Korea. Why don’t you give it a rest?’ But honestly, I think the day he gives it up is the day he dies.”

As the weekend festivities wrap up and everyone is preparing for the long trip home, Brown tells me that no matter what happens, he isn’t worried.

“You’ll always stay relevant as long as you can shoot a gun.”