Meet The Custom Motorcycle That Honors a Legendary Yamaha Rally Bike

Fans of Yamaha’s iconic XT500 and SR500 bikes will covet this bespoke beauty.

It’s 1977. French motorcycle racer Thierry Sabine is missing in action in the Libyan desert on the Abidjan-Nice Rally.

“I realize that my situation is uncomfortable, difficult,” Sabine later wrote. “Two days later I have no compass or clock, which broke down in a fall while trying to find the lost route. It is now two days and two nights that I am lost in the desert, under a sun that begins to make me lose my mind. The total absence of shadow is an oppressive sensation, which engenders a feeling similar to that of claustrophobia. Then I decide to get away from my bike. In socks and sucking the stones to give me saliva, I realize my life is worth less and less. And that is when I promise that if I come out alive from this experience I will sweep away as much superficiality as my existence contains.”

Luckily his friend Jean Michel Siné spotted him from his helicopter, and rescued him. Most mere mortals would take this lesson and move on to less heroic things. But Sabine was made of sterner stuff. Years later he correctly described what he created as a result, as “a challenge for those who go, a dream for those left behind.” What he created was, of course, the legendary Paris-Dakar Rally.

Launched in 1978 with an entry fee of 4.50 francs—about $1 at the time—at the start line at the Place du Trocadéro in Paris, Sabine told the entrants, “In this test, you come to seek strong emotions, not perishable memories. I offer you all that, but I don’t want to hide the risks you’ll be taking. You accept it and you are also the ones who have to assume it.”

192 vehicles started the race that first year. Only 74 finished. Over two continents, six countries, 10,000 km and 16 days, more than 60%of the entrants crashed out or broke down. The overall winner would be a 21-year-old Frenchman, Cyril Neveu, riding a Yamaha XT500. Neveu later commented that, “I was 21 years [and] I was just like everyone else, a simple guy grabbing onto the handlebars of his XT 500 without any leather satchels.”

But his strategy was different. And the Paris-Dakar was not his first North African rodeo. He had competed in the same Abidjan-Nice Rally as Sabine the year before. And decided he would take Sabine’s lead for the upcoming Paris-Dakar by investing in a Yamaha XT500.

The XT500 wasn’t fast. But it was strong. And it was reliable. In a true rendition of “The Hare and the Tortoise,” Neveu was careful and slowly made his way up the ranks gaining positions as other entrants broke down; closing the 19-minute gap to leader Patrick Schaal when Schaal fell and broke his finger somewhere between Gao and Mopti in Mali. He crossed the line first overall. And did the same thing again the next year, again on a Yamaha XT500. Securing his place, and the XT500’s place, in history. Neveu went on to win five times. And the Yamaha XT500 went on to become one of the most legendary production bikes of all time, in the form of the road going version, the SR500.

What had made the XT500 perfect for the Paris-Dakar was its mule-like unbreakability and reliability in tricky terrain. Fancy it wasn’t. But beautiful in its simplicity it was. The XT500 was a new foray for Yamaha—into the world of “enduro” bikes. At home both on and off road. They were well thought out, designed, and tested, with magical simplicity. A 499cc single cylinder motor with one cam, one inlet, one exhaust, and one carburetor produced 28bhp at the rear wheel—enough to catapult it to nearly 100 mph on the road. The engine casings were vertical like British bikes at the time.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBnV1o1l0z_

But, unlike the British bikes, they were almost leak-proof. Two oil pumps ensured the moving parts were always well lubricated, with the oil being stored in the frame itself so the bike was slim and agile. Precision bearings were used liberally to reduce friction and heat. And the 15-plate wet clutch would take more punishment in thick sand than the Sahara could throw at it. Perhaps the coolest little touch was the inclusion of a kickstart with a button on the handlebars to release compression, and a window to see where the piston was so that even a novice could start the engine, sandstorm or snow, in a few kicks.

The XT500 was the personification of the right tool for the job when it came to going off-road in the late 1970s and early ’80s. So when Yamaha wanted to create their own version of the British thumpers like the Manx Norton, they decided to use the XT500 as a base. And turn it into a proper road bike. Thus the SR500 was born. The SR500 relied upon the same basic, reliable engine as the XT500. It was so enjoyable to ride that Motorrad, a German motorcycle magazine, voted it Moto of the Year in both 1978 and 1979.

The SR500 went on to slowly win hearts and minds across the globe, remaining in production until 1999. Its smaller brother the SR400, originally created for the Japanese market in 1978, still remains in production today. So you can still buy a new one. Or you can buy one of these. The Autofabrica Type 7X.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CAdTJswlNhC

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder. And I’m a superbike kind of guy. But you’d have to be blind not to take in the seductive lines of this marvel of machinery. Pay particular attention to the upswept exhaust. And moreover the attention to detail and rider experience engendered by the extremes the Autofabrica team visited to stop you scorching the family jewels as you dismount: Ceramic coated pipe, enveloped in a cooling air-channel crafted into the fuel tank, and covered by a heat shield and a perforated guard. Make no mistake, these guys are leaving nothing to chance.

The London-based bespoke restomod shop takes the SR500 to what may be its ultimate evolution. With their handmade bespoke ethos, keen eye for proportion, color and ergonomic design, coupled with a strong sense of timeless style, this just may have been the bike Steve McQueen should have used to jump the fence in The Great Escape. And at the very least it shares the DNA of perhaps the greatest desert bike of all time.

Commission yours now. Before we beat you to it.

Specifications

https://www.instagram.com/p/B8l_pAalTzU

- Price: About $37,000

- Base model: Yamaha SR500

- Engine: 515cc, fully rebuilt

- Frame: Lightened, de-lugged, and rear loop modification

- Electrics: New wiring loom, uprated headlight and taillight LED indicators

- Exhaust: Hand bent steel with ceramic coating

- Suspension: Front uprated internals, rear uprated shocks

- Wheels: 18” front, 18” rear, replaced with stainless steel spokes

- Bodywork: One-off hand made aluminum tank, hand trimmed seat, hand made aluminum front and rear fenders, hand sculpted aluminum exhaust guard

- Color and Trim: Unique grey/green paintwork, black suede seat with brushed aluminum detail

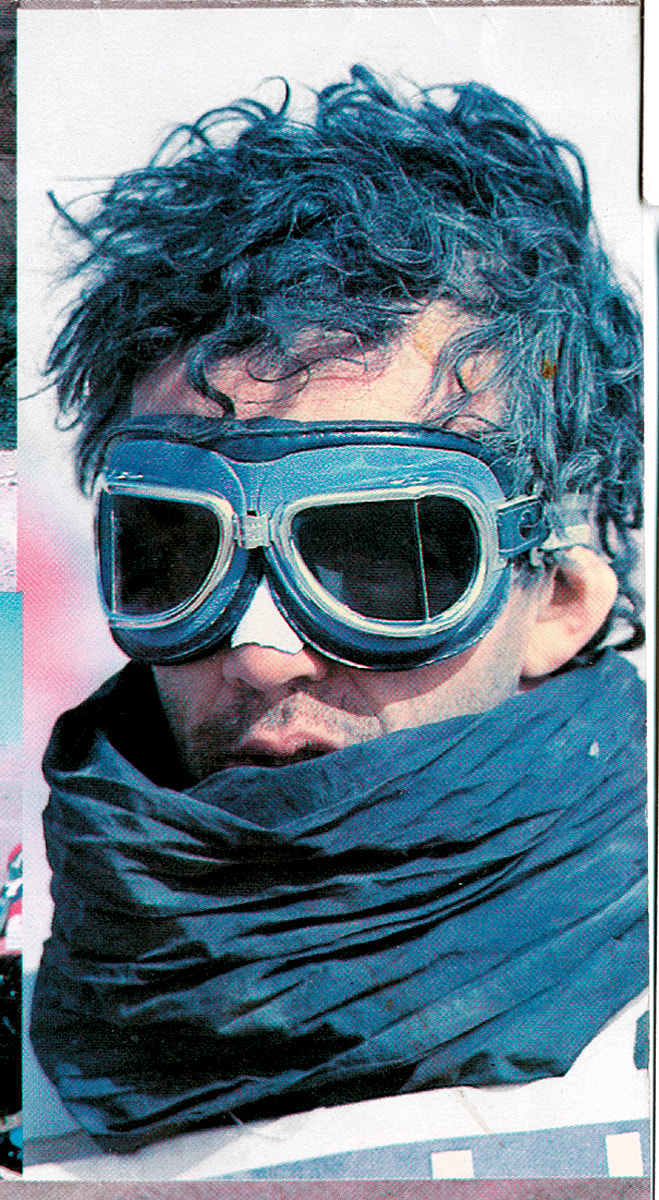

Legendary Lensman Gilles Bensimon Recalls Racing the Paris-Dakar

The early days of the Paris-Dakar were for adventurers. Just ask famed photographer Gilles Bensimon, Maxim’s own Special Creative Adviser. He was there for its anarchic beginning. Before corporate sponsorship, back when it was a race against yourself, the elements, and the locals. Hoping the machinery you had personally wrenched together with your team stood up to the abuse. And that you didn’t break down, get lost, or get murdered en route.

Gilles entered the race three times, and finished once. As we’ve perhaps made abundantly clear these races were not for wimps. He went straight from the finish to a plane and back to France. He left his bike. He left his kit. He left everyone. No party. No whooping it up. Just survival.

He’d used some money inherited from his grandfather to put his team together; and to build his bikes. The Bensimon team modified a Yamaha XT500 the first year, boring it out to 650cc and making further modifications to suspension and fuel tank in addition to a custom Barigo frame. But it was not to be a successful campaign. Gilles says he should have left the XT500 stock. Or even used an XT400. Lighter, easier to lift and manipulate around.

This was before GPS, and before cellphones; a paper map and a compass were your only edge. “If you got lost, you really got lost,” as Gilles says, “nobody knew where you were”—people died. In fact, he compares running the early Paris-Dakar to “trying to kill yourself.” And after every race he would fly straight home, “never in the mood” for a big party, or to celebrate. But after a few months, “you wanted to go back…it’s like a bad addiction.”