Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About the Automotive Legend That Is Land Rover

The ultimate combination of off-road muscle and absolute luxury for almost 70 years.

As with anything in life, context is everything. To understand the genesis of Land Rover, one first must survey the smoldering landscape of its birthplace in Great Britain. It was 1947, just a few years removed from the devastation of WWII. The nation lay in rubble, infrastructure destroyed, factories barely powering back up under heavy limitations on materials, energy, and capital.

This is the setting where, on an overcast beach in Wales, brothers Maurice and Spencer Wilks found themselves discussing their next move. As board members of one of the largest automakers in the land, the Rover Car Company, there was little room for error.

Rover was then known for building sprawling luxury cars, for which there was now zero demand. Maurice grabbed a piece of driftwood, bent over the golden sand, and sketched the outline of a Jeep-like vehicle. “This,” he said, looking up at his brother as he roughly outlined the small truck. “This is what we’re going to build.”

That this sandy image looked a lot like a Jeep was no coincidence. While laboring on and clearing his Anglesey farm, Maurice had fallen in love with a surplus military Willys, his do-everything beast of choice.

Taking inventory of the countless obstacles that his company—and the nation at large—would have to overcome to slog their way out of the war-torn decade, Maurice’s idea was a wise one. “The country just came out of a massive war; it was victorious, yet the entire area was on its knees. The industry was down, there were massive issues overall, and literally no running economy,” says director of Jaguar Land Rover Classic Tim Hannig. “And so they said, ‘Look, we need to try to do something that can be a tool to help get this country back on its feet—or let’s say its wheels,'” Hannig says. “A go-anywhere, do-anything vehicle. And that was its sole purpose; it was nothing but to get around in it and be as flexible and versatile as possible.”

Compounding complications was the asphyxiating rationing of raw materials. The war industry had swooped up most available steel, making the metal rare and prohibitively expensive. Yet aluminum, widely used in the suddenly vanished airplane industry—was in surplus. So the Wilks brothers designed this four-wheel-drive prototype around what was available, using steel only where absolutely necessary (e.g., chassis, bulkhead, and engine), and incorporating only the simplest light alloy body panels to circumvent expensive presses. To optimize the vehicle for export, and to jump-start British industry, the mandate was to use as many Rover parts as possible, especially expensive R&D components like the gearbox and 1.6-liter four-cylinder engine. They even shaved pennies with the paint, a hue dubbed Grasmere Green, reputed to have been salvaged from surplus aeronautics.

So the Wilkses built a rough prototype with central steering, both to save money, by not having to develop both left-and right-hand drive models, and to appeal to tractor-acclimated farmers. Development was accelerated beyond comprehension: From that first beach sketch, the vehicle was designed, engineered, tested, and produced in one calendar year. It debuted in April 1948 at the Amsterdam Motor Show. The initial 48 preproduction vehicles were a landmark.

What came next not even Maurice could have dreamed in the happiest moments pulling stumps on his Welsh farm. “It hit like lightning, with a demand they had never anticipated,” Hannig says. “They just could not make them fast enough.”

Ends of the Earth

As the chariot of choice for traversing the fading British colonial empire, Land Rover had established its off-roading foundations early on. But the brand set itself apart with a series of expeditions that immediately separated it from all pretenders.

In 1954 Land Rover participated in the Oxford and Cambridge Trans-Africa Expedition, in which two teams of university students raced 86″ Land Rover Series I station wagons across 25,000 miles of Africa, from Egypt to Cape Town and back. The following year the Oxford and Cambridge Far Eastern Expedition traveled from London to Singapore, an absolutely brutal, never-before-done campaign that defined Land Rover’s abilities to plumb well beyond the edges of civilization.

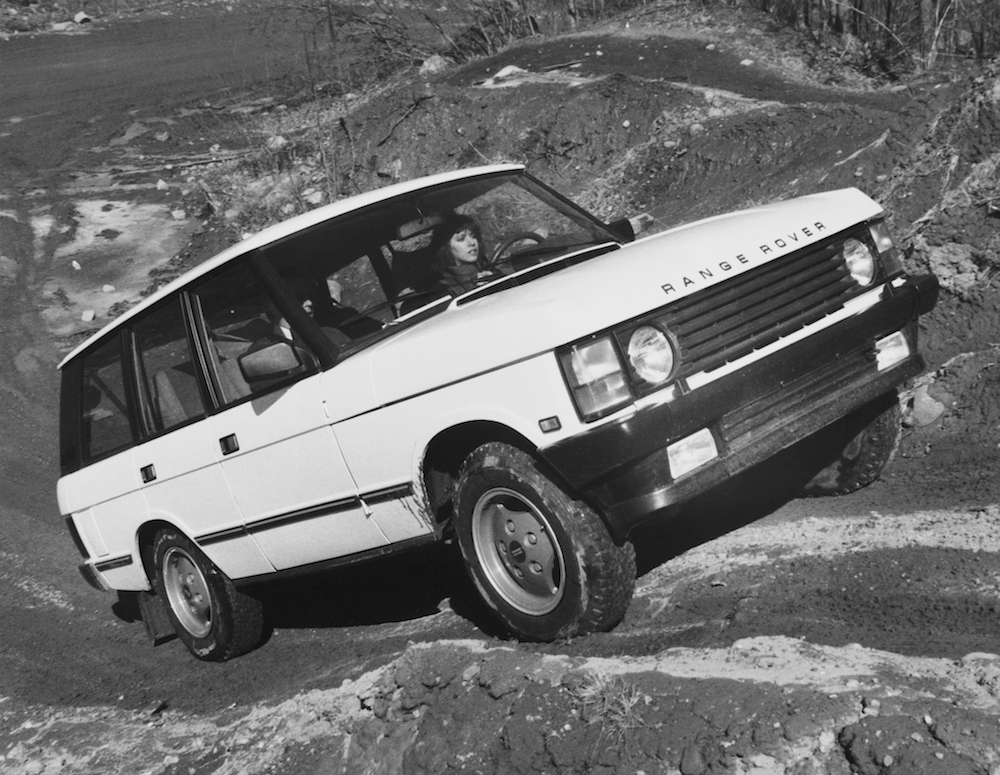

Harnessing this pedigree, Rover returned for the British Trans-Americas Expedition in 1971 and 1972 to prove the off-road integrity of its nascent Range Rover model. The punishing voyage traversed 18,000 miles from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego, crossing harrowing terrain including the roadless Darién Gap, previously thought to be impenetrable. Led by the British military, the team bridged

the Panama and Colombia border and later crossed the finish

line in Chile.

In 1980, the most famous Rover-centric expedition, the Camel

Trophy, was born. It soon earned the title “the Olympics of off-roading.” Developed to demonstrate the surreal capability of off-road vehicles, every year the Camel Trophy aimed to conquer the Earth’s most remote corners. In 1981 several teams crawled their way through 1,000 miles of Sumatran jungles. Then eight teams crossed Papua New Guinea.

The topography the Camel Trophy attempted to negotiate was so challenging it famously forced teams to work together to survive, fording dangerous rivers and penetrating uncharted rain forests. Expeditions through Zaire, Borneo, Australia, Madagascar, Siberia, and Sulawesi followed.

It is here, under the crucible of the planet’s most trying terrain,

that Land Rover matured from sturdy off-road machine into the unrivaled icon that it is today.

And so the Land Rover was born. The boxy, crude, 8-bit stamped metal creature you’ve fallen in love with through grainy black-and-whites—mud-splattered and over-coming unbreachable obstacles—that was no object of design. Or rather, it was an object of pure design, of an almost Bauhausian obedience to function over form. Make it capable to an ideal, use as many bin parts as you can, and make it as affordable as possible.

For the first years of the Land Rover’s existence, every few weeks tweaks were made. Created in just 12 months, its design, construction, and production all evolved on the fly. So a Land Rover built in April could be significantly different than one built in August. “There was no luxury behind it; there was no performance behind it,” notes Hannig. “It was purely and only about capability.”

The Land Rover’s capability was so pure and pervasive (52 horsepower, 23 mpg, 60 mph top speed) that word of this feisty British four-wheeler spread like a postwar meme. During that era England was still profoundly connected to its commonwealth, so exports to Australia, New Zealand, India, and throughout Africa exploded; within a year they were exporting to nearly 70 nations. This is where the Land Rover mythos was made, rolling over the vast Serengeti in search of big game; clawing its way through uncharted jungles chased by locals; breaching golden Saharan dunes; whisking Winston Churchill or Queen Elizabeth or Ernest Hemingway to the edge of the empire. It is said that for one third of the world’s population, the Land Rover was the first mechanized vehicle they ever saw.

As many as 150 varietals were available from the factory during that decade, including ambulances, pickups, armored cars, station wagons, and lightweight versions built for airdropped delivery. Maybe 50 were built with welding stations installed to work on trains and remote repairs, as were 340 fire engines, fully equipped with pumps, hoses, and flashing red beacons. One delivered to Norway in 1953 was only recently retired. Thanks to an entrepreneurial Scottish company that configured Land Rovers with tank-like treads to better negotiate the sodden soil, the Cuthbertson edition was born.

Enter the Series II

As utilitarian as the Land Rover was, it soon became apparent the company would have to build a newer model with a diesel option, which was the preferred fuel on farms. The Series I was also rough around the edges and even rougher on riders.

“I do not want to discredit anything that was ever done by the company, but it wasn’t the smoothest of all rides,” Hannig admits with a tinge of guilt, as if mentioning any Rover deficiency were some sort of British sacrilege. “So they needed to sort all the issues they accumulated with it and create an upgraded version.”

In 1958 the Series II debuted, retroactively dubbing its predecessor the Series I. The standard wheelbase increased from 80 inches to 88. A bigger rear window, nonscratch glass, and rounded quarter rear windows were added for better visibility, as were such luxuries as exterior door handles and locks. It was made easier to drive thanks to a new synchromesh gearbox that eliminated the need to double clutch into second gear. By 1959, the 250,000th Land Rover rolled off the assembly line, and by April 1966 sales had doubled to a half million.

“It actually started off as a tool. And I think this is important to understand: The undisputable emotional connection that people have with Land Rover is not necessarily because the car is so special mechanically or technically, but it is because of what memories they have with the car,” says Hannig. “The Land Rover is the car that people learned to drive in on their farms, that rescued them from lions in water holes, that actually brought the help when they were in trouble and rescued them out of the snow. It’s the Land Rover that did it.

“

“So this emotional love affair people have with Land Rover is all about what you can do through one. The car is a pretty rough tool, and it always was a pretty rough tool.” Hannig pauses for a moment, before adding: “All that changed with the Range Rover; that is a different animal.”

The Dawn of the Luxury SUV

After decades of relative global dominance, Land Rover knew it was time to make its next sketch in the sand, and the company’s inner circle set out to develop a more civilized utility vehicle. Under the leadership of Gordon Bashford and Charles Spencer “Spen” King, Land Rover began experimenting with a more comfortable, car-like vehicle that still offered all the off-road capability of the Land Rover. A decade earlier Bashford had experimented with one that used Rover’s station wagon as its base, but that experiment halted in 1958. In 1966, it began anew.

Regardless of Land Rover’s worldwide success, in America Jeep was king. And as the 1960s wore on other proto-SUVs, like the International Harvester Scout, Ford Bronco, and Chevy Blazer, were also making noise, and, on the U.S. market, were presumably doing so for far less money than the British product. So under the code name Velar (derived from the Latin for “to veil” or “to cover”), Bashford, King, and company built 26 prototypes, camouflaged at the time to hide them not only from nosy pedestrians but also dubious Rover board members.

Finally, in June of 1970, Land Rover unveiled the Range Rover. Bearing an unrivaled suspension of long-travel coil springs, permanent four-wheel drive with a vacuum-operated center differential, a 215-cubic-inch V-8, and safety technology such as disc brakes and seat belts, the Range Rover—much like its Land Rover predecessor—revolutionized the automotive landscape. For the first time, a truly capable off-road vehicle boasted car-like handling and manners.

The simple, clean-line design of the Range Rover was so revolutionary that it garnered awards and was displayed at the Louvre as a totem of superb design. When the Range Rover was finally introduced to the United States in March of 1987, it offered real luxuries—novel in a truck— like power seats, a leather-swathed interior, wood trim, and a premium stereo. The age of the luxury SUV was born.

Holland & Holland Range Rover

Roll around the palm-studded boulevards of Los Angeles in the apex Range Rover model, the SVAutobiography, and you’ll enjoy an intoxicating degree of luxury—one usually reserved for the TMZ-baiting crowd. Developed by Jaguar Land Rover’s esteemed Special Vehicle Operations (SVO) unit, the interior is the apotheosis of luxury for an SUV (e.g., foldout aluminum tray tables, Champagne cooler, sliding panoramic roof, electric sunblinds, etc.), powered by a growling 550- or 557-horsepower supercharged V-8. While unwanted attention is minimized thanks to subtle exterior badging and famously reserved British styling, first-class attention from valets is still all but guaranteed.

But because enough is never enough in the rarefied world of ultra-luxe, the SVO team develops even further considered vehicles for those seeking, well, more. One such opus, the exclusive Holland & Holland edition, elevates bespoke attention to the next level. The collaboration with the venerated British gunmaker is finished in Holland & Holland’s signature green custom paint formulation, and features an interior swathed in deep espresso and tan leather, the buttery hide covering acres of cabin including the dashboard, doors, and transmission tunnel. French walnut-veneer trim accents the interior and comes from a single piece of wood, much like the stocks on a pair of oil-rubbed Holland & Holland rifles or shotguns.

To further advance the brand messaging, the Holland & Holland logo can be found carved into the console, intricately engraved onto pull handles along with an acanthus scroll design, embroidered on seats, and on door and tailgate badges. There are deployable walnut tables in the reclining Executive Class seats in the back, as well as a 29-speaker Meridian Audio stereo and interior mood lighting.

The most singular element of the Holland & Holland Range Rover edition, however, is the aluminum rifle and shotgun cabinet tucked in the trunk. The leather-trimmed locker is lined in matching espresso Alcantara, and is custom-built to neatly store a pair of firearms for weekend trips into the misty countryside. Harris Tweed hunting jackets are not included.

Addition by Subtraction

Now with its latest clean-sheet model, Range Rover segues into a new phase in its design paradigm. With the Velar—named in homage to those first veiled prototypes—the goal of Land Rover’s chief design officer, Gerry McGovern, was to modernize the brand’s DNA, in the truest sense of the word. In the vein of modernism, which transformed the visual language of architecture, furniture design, fine art, fashion, music, and more in the mid-20th century, McGovern embodied the philosophy by reducing the Range Rover’s aesthetics to only the most necessary elements.

Unnecessary lines were deleted, extraneous bells and whistles removed; the Velar is Range Rover distilled into its purest form. “Everything is left bare, carved from the solid; it’s more about taking what you’ve got and honing them to precision,” says McGovern of the Velar, and more holistically of Range Rover’s reductionist mandate. And one can expect that as each model evolves into its next generation, this modernization will work its way across the Range Rover landscape. Might the already gorgeous Evoque be next?

But don’t get it twisted: The Velar is not a precious objet d’art. “My job as the sort of spiritual leader of the brand is not just about where I’m taking the brand visually. When it comes to design it isn’t just about the appearance; it’s about the way it functions, it’s about the versatility, it’s about the way you use the vehicle. Design and engineering are at one,” McGovern argues. As McGovern is aware, design may be the most salient factor in Range Rover’s newest, shiniest model, but it is hardly the most important one.

Those who know what defines a Land Rover—well, they know. They look at any Range Rover and see right past the sumptuous leather and walnut comforts, the intricately knurled aluminum switchgear, high-tech gadgetry, and other indulgences, and see instead a tool of great utility. One that was engineered not with luxury as its sole motivation but rather an undying directive to be the most useful, dutifully capable, and unstoppable off-road vehicle on the planet. And while it’s unlikely most will ever know about Maurice Wilks and his sketch on that soggy Welsh sand, they most definitely will feel his mandate.